What do you want to learn more about?

Asian American Heritage Month: Interview with Jenny Wang, Ph.D, Licensed Psychologist

This week, I had the pleasure of interviewing Jenny Wang, Ph.D a Licensed Psychologist in Houston, Texas, and the creator of the Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Therapist Directory.

Please tell us a bit about yourself

I am a first-generation Taiwanese American licensed psychologist in Texas and North Carolina. I currently have a private practice in Houston, Texas where I work exclusively with women’s mental health issues across the lifespan. I am extremely passionate about reducing the stigma surrounding mental health in Asian communities and run the Instagram account @asiansformentalhealth to promote awareness regarding Asian American mental health needs and unique immigrant experiences.

Please tell us about the Asian Pacific Islander Desi American (APIDA) Therapist Directory and why you started it?

The Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Therapist Directory was born out of the struggles that I observed for so many Asian communities in seeking mental health care. The stigma against mental health is already a formidable barrier to treatment for Asians, but once they overcome the stigma, they often find that they don’t know how or where to seek out mental health professionals who are well versed in the cultural nuances that impact mental health in Asian communities. The goal of this directory is to increase the likelihood that Asian Americans seek out mental health care.

Immigrants to the United States are an incredibly diverse group, yet they share some common experiences in terms of loss, resiliency, and challenges with acculturation. What do you think are some unique challenges and strengths that Asian immigrants experience?

Asian American communities entered this country at very different time points in history and experienced unique struggles during each time period. These historical traumas include the Chinese Exclusion Act, Japanese Internment Camps, and the murder of Vincent Chin, to name a few. However, some similar themes include intergenerational conflict due to acculturative stress, difficulties with discussing emotions, trauma, and psychological difficulties, and experiences of racial trauma within a majority culture.

These struggles are not unique to Asian immigrants; however, they are confounded with the Model Minority Myth, which is a construct that primarily impacts Asian Americans in America. This myth perpetuates the idea that Asian Americans must not have as much struggles as compared to their Black and Latinx counterparts and drives a divisive spirit between marginalized people of color. The myth also incorrectly perpetuates this idea that all Asians are highly educated, high-income earners, which is simply not the case. Furthermore, by touting Asian Americans as Model Minorities, it has eventually rendered our intercultural struggles as largely unseen and our voices have been unheard for a long time.

Immigration has been on the news a lot lately. However, whenever there is a story about immigration, news channels usually only portray one type of immigrant (Spanish-speaking, from Mexico or Central America). Why do you think that is and why are Asian immigrants not featured more often?

I believe that media portrayals of immigrants is largely influenced by the political agenda and issues of the current time. When Asian Americans were first arriving to America in the mid-1800s to build the Transcontinental Railroad, there was a lot of anti-Asian immigrant propaganda similar to what is seen about Latin immigrants in our current time. But currently, immigration from Asian countries may not be seen as much of a threat to the economy or job security in the US.

However, Asian Americans are actually considered the first illegal immigrants because they were barred from naturalized citizenship by the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which is the first piece of legislation to ever exclude an entire ethnic group.

Currently, Asian immigrants are not featured more often because there is simply another more salient focus in this current time. However, with the pandemic and the anti-Asian and Chinese sentiment, people have increased their wariness of Asian exchange students and professionals entering the US.

According to the US Department of Homeland Security’s Yearbook of Immigration Statistics in 2018, 36% of the total number of individuals granted asylum were from Asia, which represents the most common region of the world for asylum seekers. Does that number surprise you?

Given that Asia includes parts of “West Asia” or what is also known as parts of the Middle East, this number does not surprise me. According to the US Department of Homeland Security countries such as Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, and Uzbekistan to name a few are included under the catchment of “Asia.” The term “Asia” is largely defined by geopolitical constructs instead of cultural or ethnic similarities.

Knowing that the largest percentage of individuals granted asylum are from Asia, what do you think are some unique challenges they may face? What are some cultural perspectives that clinicians should keep in mind when working with this population?

In reference to the above question, the difficulty in working with individuals from “Asia” is that it comprises of a huge breadth of cultures, languages, religions, and ethnic groups. This means that simply being “Asian” myself does not even necessarily equip me to work with all the individuals who fall under the category of “Asian.” As a result, clinicians are tasked with the responsibility to do several things.

Firstly, we must listen well. Even if I am working with a Taiwanese client, I can never make assumptions that I understand this individual’s experiences or background. As such, we must listen with openness and curiosity.

Second, we must check and recheck our own implicit biases and assumptions. The most glaring errors occur when clinicians do not maintain a posture of teachability from our clients about their history, culture, background and narratives. We must realize that there is a difference between being overtly biased and implicitly biased and refraining from being overtly biased is not enough. We must go further to question and test our assumptions with each and every client we are serving.

Third, working with Asian Americans (or really any immigrant) means that we need to be sensitive to how Western psychology may directly or indirectly pathologize cultural practices or dynamics. For example, some cultures have kids who sleep with their parents into early childhood and this may be seen as negative from a Western parenting perspective. However, this practice is highly culturally influenced and may reflect a culture’s focus on interdependence and community. These sensitivities take time to develop, which is why consulting with mental health professionals from all backgrounds is a must if working in communities of color.

Another area of focus for immigration psychological evaluations is family preservation. Immigration evaluations are often used in extreme hardship waivers or when a family member is in removal proceedings (deportation process). The focus of these evaluations is to assess the relationship between members of a family. What are some characteristics that make Asian families strong and what are some things that clinicians should focus on when assessing relationships within Asain families?

Asian families tend to have more collectivist values, but this also depends on their level of acculturation and exposure to Western values. This means that they think of their family members as important parts of each decision made. In fact, independence is sometimes seen as a threat to the family goals and values. Understanding how a specific family negotiates issues with boundaries, independence, decision-making, help-seeking behaviors, etc becomes paramount because we cannot assume we know how these values play out day today.

For example, for some adult individuals, appropriate boundary setting is not telling their parents every single detail about their lives because the cultural clash would be so great and the individual is not ready yet to create ruptures in their family. Conversely, in cases where there is domestic abuse or violence or history of sexual assault by an American citizen on an immigrant, a clinician must be aware of the sensitivities surrounding an individual’s willingness to disclose and report these incidents and well as the potential risk of retaliation by the perpetrator of abuse on an immigrant.

As mental health professionals, we must hold space for these complexities and create safe spaces for individuals in which to trust us and then speak their truth. It is a difficult task, but one in which we must diligently pursue in order to serve marginalized people of color.

Thank you again, Jenny, for taking the time to chat with me, and share your experience and insight!

More information about Jenny Wang, Ph.D. can be found here. Also be sure to check out the Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Therapist Directory, where you can join the directory and/or use it as a powerful referral source.

I’m Cecilia Racine, and I teach therapists how to help immigrants through my online courses. As a bilingual immigrant myself, I know the unique perspective that these clients are experiencing. I’ve conducted over 500 evaluations and work with dozens of lawyers in various states. Immigrants are my passion, I believe they add to the fabric of our country.

related articles

Building Rapport with Clients in Immigration Cases

Establishing a strong therapeutic alliance is critical and challenging for mental health clinicians working with…

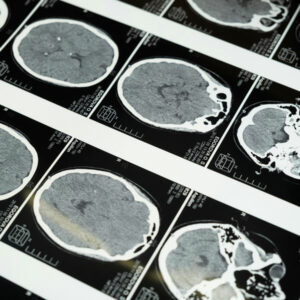

Invisible Wounds: The Importance of Brain Injury Awareness in Psychological Evaluations for Immigration Cases

March marks National Brain Injury Awareness Month, an essential time for mental health clinicians to…

Budget-Friendly Tips for Professional-Looking Photos

As therapists dedicated to helping individuals through crucial immigration processes, presenting a professional image is…

Join the Free

Immigration evaluation

therapists facebook group

Are you a therapist that conducts immigration evaluations?